Sunday, August 31, 2008

Shameless Self Promotion

Dude. Someone just told me that my Arch Park Wonderland image was an "Editor's Choice" on the National Association of Photoshop Professionals (NAPP) site. That's pretty cool. That's the second time I've been selected in the past few months. Congratulate me! Now if only someone would pay me the big bucks for an image. Yeah, right.

Bill Kristol on Palin

Why the left is scared to death of McCain's running mate.

by William Kristol

The Weekly Standard, 09/08/2008, Volume 013, Issue 48

A spectre is haunting the liberal elites of New York and Washington--the spectre of a young, attractive, unapologetic conservatism, rising out of the American countryside, free of the taint (fair or unfair) of the Bush administration and the recent Republican Congress, able to invigorate a McCain administration and to govern beyond it.

Let Palin Be Palin That spectre has a name--Sarah Palin, the 44-year-old governor of Alaska chosen by John McCain on Friday to be his running mate. There she is: a working woman who's a proud wife and mother; a traditionalist in important matters who's broken through all kinds of barriers; a reformer who's a Republican; a challenger of a corrupt good-old-boy establishment who's a conservative; a successful woman whose life is unapologetically grounded in religious belief; a lady who's a leader.

Let Palin Be Palin That spectre has a name--Sarah Palin, the 44-year-old governor of Alaska chosen by John McCain on Friday to be his running mate. There she is: a working woman who's a proud wife and mother; a traditionalist in important matters who's broken through all kinds of barriers; a reformer who's a Republican; a challenger of a corrupt good-old-boy establishment who's a conservative; a successful woman whose life is unapologetically grounded in religious belief; a lady who's a leader.

So what we will see in the next days and weeks--what we have already seen in the hours after her nomination--is an effort by all the powers of the old liberalism, both in the Democratic party and the mainstream media, to exorcise this spectre. They will ridicule her and patronize her. They will distort her words and caricature her biography. They will appeal, sometimes explicitly, to anti-small town and anti-religious prejudice. All of this will be in the cause of trying to prevent the American people from arriving at their own judgment of Sarah Palin.

That's why Palin's spectacular performance in her introduction in Dayton was so important. Her remarks were cogent and compelling. Her presentation of herself was shrewd and savvy. I heard from many who watched Palin--many of them not predisposed to support her--about how moved they were by her remarks, her composure, and her story. She will have a chance to shine again Wednesday night at the Republican convention.

But before and after that, she'll be swimming in political waters infested with sharks. Her nickname when she was the starting point guard on an Alaska high school championship basketball team was "Sarah Barracuda." I suspect she'll take care of herself better than many expect.

But the McCain campaign can help. The choice of Palin was McCain's own. Many of his staff expected, and favored, other more conventional candidates. The campaign may be tempted to overreact when one rash sentence or foolish comment by Palin from 10 or 15 years ago is dragged up by Democratic opposition research and magnified by a credulous and complicit media.

The McCain campaign will have to keep its cool. It will have to provide facts and context, and to hit back where appropriate. But it cannot become obsessed with playing defense. It should allow Palin to deal with the charges directly and resist the temptation to try to shield her from the media. Palin is potentially a huge asset to McCain. He took the gamble--wisely, we think--of putting her on the ticket. McCain's choice of Palin was McCain being McCain. Now his campaign will have to let Palin be Palin.

There will be rocky moments. But they will fade if the McCain campaign lets Palin's journey take its natural course over the next two months. Millions of Americans--mostly but not only women, mostly but not only Republicans and conservatives--seemed to get a sense of energy and enjoyment and pride, not just from her nomination, but especially from her smashing opening performance. Palin will be a compelling and mold-breaking example for lots of Americans who are told every day that to be even a bit conservative or Christian or old-fashioned is bad form. In this respect, Palin can become an inspirational figure and powerful symbol. The left senses this, which is why they want to discredit her quickly.

A key moment for Palin will be the vice presidential debate, to be held at Washington University in St. Louis on October 2. One liberal commentator--a former U.S. ambassador and not normally an unabashed vulgarian--licked his chops Friday afternoon: "To steal an old adage of former Secretary of State James Baker . . . putting Sarah Palin into a debate with Joe Biden is going to be like throwing Howdy Doody into a knife fight!"

Charming. And if Palin holds her own against Biden, as she is fully capable of doing, McCain will then have succeeded in combining with his own huge advantage in experience and judgment, a politician of great promise in his vice presidential slot who will make Joe Biden look like a tiresome relic. McCain's willingness to take a chance on Palin could turn what looked, after Obama's impressive speech Thursday night in Denver, like a long two months for Republicans and conservatives, into a campaign of excitement and--dare we say it?--hope, which will culminate on November 4 in victory.

--William Kristol

http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/015/500wrhjq.asp?pg=2

by William Kristol

The Weekly Standard, 09/08/2008, Volume 013, Issue 48

A spectre is haunting the liberal elites of New York and Washington--the spectre of a young, attractive, unapologetic conservatism, rising out of the American countryside, free of the taint (fair or unfair) of the Bush administration and the recent Republican Congress, able to invigorate a McCain administration and to govern beyond it.

Let Palin Be Palin That spectre has a name--Sarah Palin, the 44-year-old governor of Alaska chosen by John McCain on Friday to be his running mate. There she is: a working woman who's a proud wife and mother; a traditionalist in important matters who's broken through all kinds of barriers; a reformer who's a Republican; a challenger of a corrupt good-old-boy establishment who's a conservative; a successful woman whose life is unapologetically grounded in religious belief; a lady who's a leader.

Let Palin Be Palin That spectre has a name--Sarah Palin, the 44-year-old governor of Alaska chosen by John McCain on Friday to be his running mate. There she is: a working woman who's a proud wife and mother; a traditionalist in important matters who's broken through all kinds of barriers; a reformer who's a Republican; a challenger of a corrupt good-old-boy establishment who's a conservative; a successful woman whose life is unapologetically grounded in religious belief; a lady who's a leader.So what we will see in the next days and weeks--what we have already seen in the hours after her nomination--is an effort by all the powers of the old liberalism, both in the Democratic party and the mainstream media, to exorcise this spectre. They will ridicule her and patronize her. They will distort her words and caricature her biography. They will appeal, sometimes explicitly, to anti-small town and anti-religious prejudice. All of this will be in the cause of trying to prevent the American people from arriving at their own judgment of Sarah Palin.

That's why Palin's spectacular performance in her introduction in Dayton was so important. Her remarks were cogent and compelling. Her presentation of herself was shrewd and savvy. I heard from many who watched Palin--many of them not predisposed to support her--about how moved they were by her remarks, her composure, and her story. She will have a chance to shine again Wednesday night at the Republican convention.

But before and after that, she'll be swimming in political waters infested with sharks. Her nickname when she was the starting point guard on an Alaska high school championship basketball team was "Sarah Barracuda." I suspect she'll take care of herself better than many expect.

But the McCain campaign can help. The choice of Palin was McCain's own. Many of his staff expected, and favored, other more conventional candidates. The campaign may be tempted to overreact when one rash sentence or foolish comment by Palin from 10 or 15 years ago is dragged up by Democratic opposition research and magnified by a credulous and complicit media.

The McCain campaign will have to keep its cool. It will have to provide facts and context, and to hit back where appropriate. But it cannot become obsessed with playing defense. It should allow Palin to deal with the charges directly and resist the temptation to try to shield her from the media. Palin is potentially a huge asset to McCain. He took the gamble--wisely, we think--of putting her on the ticket. McCain's choice of Palin was McCain being McCain. Now his campaign will have to let Palin be Palin.

There will be rocky moments. But they will fade if the McCain campaign lets Palin's journey take its natural course over the next two months. Millions of Americans--mostly but not only women, mostly but not only Republicans and conservatives--seemed to get a sense of energy and enjoyment and pride, not just from her nomination, but especially from her smashing opening performance. Palin will be a compelling and mold-breaking example for lots of Americans who are told every day that to be even a bit conservative or Christian or old-fashioned is bad form. In this respect, Palin can become an inspirational figure and powerful symbol. The left senses this, which is why they want to discredit her quickly.

A key moment for Palin will be the vice presidential debate, to be held at Washington University in St. Louis on October 2. One liberal commentator--a former U.S. ambassador and not normally an unabashed vulgarian--licked his chops Friday afternoon: "To steal an old adage of former Secretary of State James Baker . . . putting Sarah Palin into a debate with Joe Biden is going to be like throwing Howdy Doody into a knife fight!"

Charming. And if Palin holds her own against Biden, as she is fully capable of doing, McCain will then have succeeded in combining with his own huge advantage in experience and judgment, a politician of great promise in his vice presidential slot who will make Joe Biden look like a tiresome relic. McCain's willingness to take a chance on Palin could turn what looked, after Obama's impressive speech Thursday night in Denver, like a long two months for Republicans and conservatives, into a campaign of excitement and--dare we say it?--hope, which will culminate on November 4 in victory.

--William Kristol

http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/015/500wrhjq.asp?pg=2

Saturday, August 30, 2008

Pastry Chef Becky in the News

From the current Texas Monthly:

Coco Chocolate Lounge & Bistro.

San Antonio

by Patricia Sharpe

The nerve. Another reviewer grabbed the Sex and the City image I had intended to use in writing about Coco, the tall, dark, and sensuous bistro that recently opened on San Antonio’s far north side. Now I have to trot out my second-best movie comparison: Moulin Rouge. Actually, they both work: I can see the four Sex pistols on one of Coco’s red velvet banquettes, appraising their latest boy toy while dipping ripe fruit in chocolate fondue. But I can also imagine Nicole Kidman in a scarlet gown at the bar devouring a Kiss, Coco’s diet-be-damned dessert of crème brûlée swathed in chocolate mousse

Read the entire review

Friday, August 29, 2008

Sarah Palin for President

Thursday, August 28, 2008

Political Stuff

ABC asks, Should Biden Share Blame for the Foreclosure Crisis?

Stanley Kurtz looks into link between American terrorist Bill Ayers and Obama. There's something really weird about this.

Stanley Kurtz looks into link between American terrorist Bill Ayers and Obama. There's something really weird about this.

Northern Italy in 1957

On the year of my birth wonderful things were happening all over the world.

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Image of the Day

I captured this Dragonfly yesterday out in a cornfield. All I had with me was my infrared-coverted camera and a 70-300mm zoom.

What's fascinating about this second image is the itsy-bitsy flies on the head of the dragonfly. Click on the image to see a larger version. What in the world are they doing?

What's fascinating about this second image is the itsy-bitsy flies on the head of the dragonfly. Click on the image to see a larger version. What in the world are they doing?

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Monday, August 25, 2008

Sunday, August 24, 2008

Photo Walk

Yesterday, we met in Laclede's Landing for the Scott Kelby Worldwide Photo Walk in St. Louis. We had about 45 people. We walked, talked, took pictures, shared lenses, and then ate lunch and looked at one another's images a bit. It was a blast. I'll be posting some of my images from that walk here all week. But here's the first. It's an IR (infrared) image.

Arch Park Wonderland

Arch Park Wonderland

Saturday, August 23, 2008

Capture NX 2.0 and Infrared Processing

I apologize in advance for this esoteric post on infrared post processing. But someone Googling for how to process their IR images with Capture NX 2.0 may jump for joy when he or she finds this.

After I got my IR-converted camera back I googled long and hard to find a workflow that would mimic the Blue-Green channel swap one can easily accomplish with Photoshop's channel mixer. There is no channel mixer on Capture NX 2.0, so I wondered how it might be done.

First of all, I love Capture NX 2.0. It is the best way to work with Nikon's RAW files (NEF). I use Capture NX 2.0 for all my processing and only go to PS CS3 if I need to do pixel editing (cloning, etc.).

So is there a way to process infrared NEFs with Capture NX? Yes, there is. I'm not going to tell you how to do all of the processing. Just the part that relates to images captured with your IR-converted camera. I have Nikon D70s with an "enhanced color" IR conversion from LifePixel. But what I outline here applies just as well to standard IR conversions as well. Here it is:

1. In the "Develop" section of your "Edit List" tool bar on the right, open "camera settings" and set your white balance. I do it with "set grey point" and use the marquee tool.

2. While in the "Camera Settings" go to "Picture Control" and chose "Vivid."

3. Then click the "Advanced" toggle just below "Picture Control," go to the "Saturation" slider and drag it all the way up to "9." [I'm not sure if this is the best for "standard IR conversions," but it works well for "enhanced color."]

4. Leave the "Camera Settings" and choose your white and black points (and your neutral point, if you think you need it).

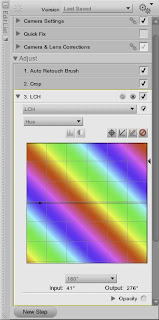

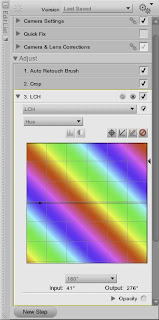

5. Now, here's the cool part. Click on the "New Step" button. Select "Color" and then "LCH" from the pull down menus.

5. Now, here's the cool part. Click on the "New Step" button. Select "Color" and then "LCH" from the pull down menus.

6. Click on the pull down menu that says "Master Lightness" and choose "Hue." That will bring up a colored hue box. Below the box there's another pull down menu. Click that and select 180. Notice that the hues have all slanted. (See the illustration to the right.)

7. Go to the triangular slider on the right side of the box. Slide it about two-thirds of the way up until the red and blue channels are switched. Watch your image. You'll want to experiment with the best place to put that slider. The red sky has now become blue.

8. Once you've done this you can tweak the image any way you want with more color points, curve adjustments, etc.

That's it. Enjoy!

After I got my IR-converted camera back I googled long and hard to find a workflow that would mimic the Blue-Green channel swap one can easily accomplish with Photoshop's channel mixer. There is no channel mixer on Capture NX 2.0, so I wondered how it might be done.

First of all, I love Capture NX 2.0. It is the best way to work with Nikon's RAW files (NEF). I use Capture NX 2.0 for all my processing and only go to PS CS3 if I need to do pixel editing (cloning, etc.).

So is there a way to process infrared NEFs with Capture NX? Yes, there is. I'm not going to tell you how to do all of the processing. Just the part that relates to images captured with your IR-converted camera. I have Nikon D70s with an "enhanced color" IR conversion from LifePixel. But what I outline here applies just as well to standard IR conversions as well. Here it is:

1. In the "Develop" section of your "Edit List" tool bar on the right, open "camera settings" and set your white balance. I do it with "set grey point" and use the marquee tool.

2. While in the "Camera Settings" go to "Picture Control" and chose "Vivid."

3. Then click the "Advanced" toggle just below "Picture Control," go to the "Saturation" slider and drag it all the way up to "9." [I'm not sure if this is the best for "standard IR conversions," but it works well for "enhanced color."]

4. Leave the "Camera Settings" and choose your white and black points (and your neutral point, if you think you need it).

5. Now, here's the cool part. Click on the "New Step" button. Select "Color" and then "LCH" from the pull down menus.

5. Now, here's the cool part. Click on the "New Step" button. Select "Color" and then "LCH" from the pull down menus.6. Click on the pull down menu that says "Master Lightness" and choose "Hue." That will bring up a colored hue box. Below the box there's another pull down menu. Click that and select 180. Notice that the hues have all slanted. (See the illustration to the right.)

7. Go to the triangular slider on the right side of the box. Slide it about two-thirds of the way up until the red and blue channels are switched. Watch your image. You'll want to experiment with the best place to put that slider. The red sky has now become blue.

8. Once you've done this you can tweak the image any way you want with more color points, curve adjustments, etc.

That's it. Enjoy!

Friday, August 22, 2008

Breaking Free, Part II

This is Part IV in my series analyzing Luther's Catechetical Doctrine of the Trinity. It's really a continuation of Part III.

Part I. Part II. Part III.

We ended last time promising more on Luther's break with medieval trinitarian speculative theology.

Over time, after the brilliant work of Augustine, the Trinity was marginalized in Western Theological thought. The Trinity lost its constitutive role in the presentation of the Christian faith. The existence and attributes of God de deo uno edged out discussions of God de deo trino.

Post-Augustinian Trinitarian theology tended to be more interested in developing a rational justification for belief in the Trinity independently of the revealed work of the Godhead in the economy of salvation. The threeness of God becomes a complicating factor, a puzzle that must be reasoned through. [BTW, I'm not taking sides in the debate about whether Augustine's doctrine of the Trinity caused this state of affairs in medieval theology. I have some concerns with, for example, Gunton's account of the genesis of the problem. My only point here is that there was indeed a problem with the church's theological formulation of the doctrine of the Trinity.]

Luther brilliantly recovers the constitutive place of the Trinity for the understanding the Christian faith. If Augustine’s ontological speculation set in motion a trend in Western theology to elevate the divine substance as the presupposition of divinity, the highest ontological principle, then, Luther emphatically breaks with that tradition.

The Trinity is for simple Christians who trust in the Persons of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, not primarily for philosophers and scholastics who are interested in logically penetrating problems arising from meditation on the substance of God. The Trinity is the gateway through which one encounters God in the Person of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Otherwise stated, the Trinity simply is not a problem for Luther. God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have no need of metaphysician-theologians to justify their existence philosophically. They have revealed themselves in their works. Luther has no interest in what had become a preoccupation in late Medieval Trinitarian theology in the West—logical method, systematic cohesion, terminological precision, and so on. Medieval theologians tended to downplay the existential and soteriological import of the doctrine of the Trinity. They were concerned with unpacking the logical and metaphysical implications of God’s threeness and oneness. These philosophical interests left the nature of the Triune God’s relationship pro homine underdeveloped (at best). The Patristic origin of trinitarian theology as a soteriological development was lost. In the Creed, however, according to Luther, we learn “to know God perfectly,” which means that we learn “what we must expect and receive from him.”

Part I. Part II. Part III.

We ended last time promising more on Luther's break with medieval trinitarian speculative theology.

Over time, after the brilliant work of Augustine, the Trinity was marginalized in Western Theological thought. The Trinity lost its constitutive role in the presentation of the Christian faith. The existence and attributes of God de deo uno edged out discussions of God de deo trino.

Post-Augustinian Trinitarian theology tended to be more interested in developing a rational justification for belief in the Trinity independently of the revealed work of the Godhead in the economy of salvation. The threeness of God becomes a complicating factor, a puzzle that must be reasoned through. [BTW, I'm not taking sides in the debate about whether Augustine's doctrine of the Trinity caused this state of affairs in medieval theology. I have some concerns with, for example, Gunton's account of the genesis of the problem. My only point here is that there was indeed a problem with the church's theological formulation of the doctrine of the Trinity.]

Luther brilliantly recovers the constitutive place of the Trinity for the understanding the Christian faith. If Augustine’s ontological speculation set in motion a trend in Western theology to elevate the divine substance as the presupposition of divinity, the highest ontological principle, then, Luther emphatically breaks with that tradition.

The Trinity is for simple Christians who trust in the Persons of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, not primarily for philosophers and scholastics who are interested in logically penetrating problems arising from meditation on the substance of God. The Trinity is the gateway through which one encounters God in the Person of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Otherwise stated, the Trinity simply is not a problem for Luther. God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have no need of metaphysician-theologians to justify their existence philosophically. They have revealed themselves in their works. Luther has no interest in what had become a preoccupation in late Medieval Trinitarian theology in the West—logical method, systematic cohesion, terminological precision, and so on. Medieval theologians tended to downplay the existential and soteriological import of the doctrine of the Trinity. They were concerned with unpacking the logical and metaphysical implications of God’s threeness and oneness. These philosophical interests left the nature of the Triune God’s relationship pro homine underdeveloped (at best). The Patristic origin of trinitarian theology as a soteriological development was lost. In the Creed, however, according to Luther, we learn “to know God perfectly,” which means that we learn “what we must expect and receive from him.”

Thursday, August 21, 2008

We're Not in Kansas Anymore, Spencer

Yesterday I finally got my IR-converted Nikon D70s back from Lifepixel. Unfortunately, it either rained or was cloudy most of the day. That's not good for IR images. The only time I got out to try it out was to capture images in my front yard with my puppy. My front yard is not the most photogenic location!

This image is silly, I know. The sky was too cloudy. The light was a bit weak. But it is what it is. Just a test. Oh, and for Spencer to masquerade as Toto he'd have to be black!

This image is silly, I know. The sky was too cloudy. The light was a bit weak. But it is what it is. Just a test. Oh, and for Spencer to masquerade as Toto he'd have to be black!

Breaking Free: Luther and Medieval Theology on the Trinity

This is Part III in my series analyzing Luther's Catechetical Doctrine of the Trinity. Part I. Part II.

It is time to examine Luther's way of teaching the Trinity.

The first thing we notice about Luther’s Trinitarian language is that something is missing. Luther consistently avoids any use of or reference to philosophical/metaphysical terms, problems, and distinctions traditionally associated with Trinitarian dogma.

Luther’s discussion of God the Father, for example, faithfully explains the text of the Apostle’s Creed using the biblical language of Father and Creator without introducing extraneous philosophical discussions about the divine essence. God is not defined in terms of his metaphysical properties, but according to what he does, specifically what he does pro homine ("for humanity"). “What is God for man? What does he do? How can man praise or portray or describe him so that man might know him?” (LC II, 10).

In answering these questions Luther makes what is for him a paradigmatic claim. He says that the answers are found in the Creed. “Therefore the Creed is nothing other than an answer and confession of the Christian. . .” The questions “what do you have for your God?” and “what do you know about him?” are both answered with reference to God’s relationship to the one asking the question. He is my Father by virtue of the fact that he created me and sustains me. As the Small Catechism puts it: “I believe that God has created me and all things; that he has given me my body and soul. . .”

The Father is the Father because he created me and sustains me. In other words, I know that he is the Father because I know what he has done for me. The Son is my Lord because I know what he has done for me. The Spirit is the Holy Spirit because of what he does for me: he sanctifies me. This kind of approach has very little continuity with the Medieval method of explaining God’s nature and existence.

What is absent from Luther’s exposition speaks volumes. For example, he shows no concern for demonstrating the intelligibility of the doctrine of the Trinity by searching for vestigia trinitatis (vestiges of the Trinity) within creation and the human soul. He provides no discussion of the “attributes” of God, no explanation of God de deo uno apart from Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, no elucidation of the problem of the one and many, no definition of the words “person” or “substance” or “relation,” no proofs of divinity of the Son or the Spirit, no extended explanation of the inter-Trinitarian relationships between Father and Son and Spirit, no treatment of the way in which each Person partakes of the divine essence (circumincessio), no argument for the monarchy of the Father, no explication of the meaning of “begetting” and “procession,” no discussion of the two natures of Christ, and, finally, he studiously avoids inquiries into and definitions of classic Trinitarian terminology (substantia, ousia, persona, hypostasis, coessentialitas, homoousios, etc.).

Unlike conventional Medieval treatments, then, Luther’s Trinitarian theology is not couched in the objective, analytic language of the academy, but the personal language of the Bible. No attempt is made to dialectically penetrate the ontological mystery of the Godhead. The threeness of God is not a complicating factor, but inexorably related to how God works in creation, redemption, and sanctification. Luther refuses to engage in speculative reflection on the Trinity cast in the language of metaphysics, that is, in terms of the philosophical issues of class and number, substance and individual, unity and plurality, etc. Nor does Luther introduce epistemological questions concerning the creaturely conceptuality of God’s essence or being.

By dumping all of this, Luther breaks radically with the medieval tradition of Trinitarian theological reflection. Schwöbel writes: “It would not be a gross exaggeration to see the mainstream of the history of Trinitarian reflection as a series of footnotes on Augustine’s conception of the Trinity in De Trinitate. Augustine’s emphasis on the unity of the divine essence of God’s triune being, his stress on the undivided mode of God’s relating to what is not God and his attempt to trace the intelligibility of the doctrine of the Trinity through the vestigia trinitatis in the human consciousness, mediating unity and differentiation, defined the parameters for the mainstream of Western Trinitarian reflection” (Trinitarian Theology Today [T&T Clark, 1995], p. 5). If Schwöbel’s observations are correct (and I believe, for the most part, they are), then Luther’s catechetical doctrine of the Trinity was something fresh and exciting, a new way of theologizing about the Trinity. By breaking with the medieval methodology and terminology, Luther opens up productive new possibilities for the church’s doctrine of the Trinity.

More on that next time.

It is time to examine Luther's way of teaching the Trinity.

The first thing we notice about Luther’s Trinitarian language is that something is missing. Luther consistently avoids any use of or reference to philosophical/metaphysical terms, problems, and distinctions traditionally associated with Trinitarian dogma.

Luther’s discussion of God the Father, for example, faithfully explains the text of the Apostle’s Creed using the biblical language of Father and Creator without introducing extraneous philosophical discussions about the divine essence. God is not defined in terms of his metaphysical properties, but according to what he does, specifically what he does pro homine ("for humanity"). “What is God for man? What does he do? How can man praise or portray or describe him so that man might know him?” (LC II, 10).

In answering these questions Luther makes what is for him a paradigmatic claim. He says that the answers are found in the Creed. “Therefore the Creed is nothing other than an answer and confession of the Christian. . .” The questions “what do you have for your God?” and “what do you know about him?” are both answered with reference to God’s relationship to the one asking the question. He is my Father by virtue of the fact that he created me and sustains me. As the Small Catechism puts it: “I believe that God has created me and all things; that he has given me my body and soul. . .”

The Father is the Father because he created me and sustains me. In other words, I know that he is the Father because I know what he has done for me. The Son is my Lord because I know what he has done for me. The Spirit is the Holy Spirit because of what he does for me: he sanctifies me. This kind of approach has very little continuity with the Medieval method of explaining God’s nature and existence.

What is absent from Luther’s exposition speaks volumes. For example, he shows no concern for demonstrating the intelligibility of the doctrine of the Trinity by searching for vestigia trinitatis (vestiges of the Trinity) within creation and the human soul. He provides no discussion of the “attributes” of God, no explanation of God de deo uno apart from Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, no elucidation of the problem of the one and many, no definition of the words “person” or “substance” or “relation,” no proofs of divinity of the Son or the Spirit, no extended explanation of the inter-Trinitarian relationships between Father and Son and Spirit, no treatment of the way in which each Person partakes of the divine essence (circumincessio), no argument for the monarchy of the Father, no explication of the meaning of “begetting” and “procession,” no discussion of the two natures of Christ, and, finally, he studiously avoids inquiries into and definitions of classic Trinitarian terminology (substantia, ousia, persona, hypostasis, coessentialitas, homoousios, etc.).

Unlike conventional Medieval treatments, then, Luther’s Trinitarian theology is not couched in the objective, analytic language of the academy, but the personal language of the Bible. No attempt is made to dialectically penetrate the ontological mystery of the Godhead. The threeness of God is not a complicating factor, but inexorably related to how God works in creation, redemption, and sanctification. Luther refuses to engage in speculative reflection on the Trinity cast in the language of metaphysics, that is, in terms of the philosophical issues of class and number, substance and individual, unity and plurality, etc. Nor does Luther introduce epistemological questions concerning the creaturely conceptuality of God’s essence or being.

By dumping all of this, Luther breaks radically with the medieval tradition of Trinitarian theological reflection. Schwöbel writes: “It would not be a gross exaggeration to see the mainstream of the history of Trinitarian reflection as a series of footnotes on Augustine’s conception of the Trinity in De Trinitate. Augustine’s emphasis on the unity of the divine essence of God’s triune being, his stress on the undivided mode of God’s relating to what is not God and his attempt to trace the intelligibility of the doctrine of the Trinity through the vestigia trinitatis in the human consciousness, mediating unity and differentiation, defined the parameters for the mainstream of Western Trinitarian reflection” (Trinitarian Theology Today [T&T Clark, 1995], p. 5). If Schwöbel’s observations are correct (and I believe, for the most part, they are), then Luther’s catechetical doctrine of the Trinity was something fresh and exciting, a new way of theologizing about the Trinity. By breaking with the medieval methodology and terminology, Luther opens up productive new possibilities for the church’s doctrine of the Trinity.

More on that next time.

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

Did Gates See this?

The blue screen of death on the opening night of the Olympics! I understand that Bill Gates was in the audience. Is that just too good or what? The Chinese where using Windows! Bwah hah hah hah. Unbelievable.

Marriage According to Kids

My daughter Becky forwarded this list to me.

HOW DO YOU DECIDE WHO TO MARRY

You got to find somebody who likes the same stuff. Like, if you like sports, she should like it that you like sports, and she should keep the chips and dip coming..

-- Alan, age 10

No person really decides before they grow up who they're going to marry God decides it all way before, and you get to find out later who you're stuck with.

-- Kristen, age 10

WHAT IS THE RIGHT AGE TO GET MARRIED?

Twenty-three is the best age because you know the person FOREVER by then.

-- Camille, age 10

HOW CAN A STRANGER TELL IF TWO PEOPLE ARE MARRIED?

You might have to guess, based on whether they seem to be yelling at the same kids...

-- Derrick, age 8

WHAT DO YOU THINK YOUR MOM AND DAD HAVE IN COMMON?

Both don't want any more kids.

-- Lori, age 8

WHAT DO MOST PEOPLE DO ON A DATE?

Dates are for having fun, and people should use them to get to know each other. Even boys have something to say if you listen long enough.

-- Lynnette, age 8 (isn't she a treasure)

On the first date, they just tell each other lies and that usually gets them interested enough to go for a second date.

-- Martin, age 10

WHAT WOULD YOU DO ON A FIRST DATE THAT WAS TURNING SOUR?

I'd run home and play dead. The next day I would call all the newspapers and make sure they wrote about me in all the dead columns

-- Craig, age 9

WHEN IS IT OKAY TO KISS SOMEONE?

When they're rich.

-- Pam, age 7

The law says you have to be eighteen, so I wouldn't want to mess with that.

- - Curt, age 7

The rule goes like this: If you kiss someone, then you should marry them and have kids with them. It's the right thing to do.

-- Howard, age 8

IS IT BETTER TO BE SINGLE OR MARRIED?

It's better for girls to be single but not for boys. Boys need someone to clean up after them.

-- Anita, age 9 (bless you child)

HOW WOULD THE WORLD BE DIFFERENT IF PEOPLE DIDN'T GET MARRIED?

There sure would be a lot of kids to explain, wouldn't there?

-- Kelvin, age 8

And the #1 Favorite is........

HOW WOULD YOU MAKE A MARRIAGE WORK?

Tell your wife that she looks pretty, even if she looks like a dump truck.

-- Ricky, age 10

HOW DO YOU DECIDE WHO TO MARRY

You got to find somebody who likes the same stuff. Like, if you like sports, she should like it that you like sports, and she should keep the chips and dip coming..

-- Alan, age 10

No person really decides before they grow up who they're going to marry God decides it all way before, and you get to find out later who you're stuck with.

-- Kristen, age 10

WHAT IS THE RIGHT AGE TO GET MARRIED?

Twenty-three is the best age because you know the person FOREVER by then.

-- Camille, age 10

HOW CAN A STRANGER TELL IF TWO PEOPLE ARE MARRIED?

You might have to guess, based on whether they seem to be yelling at the same kids...

-- Derrick, age 8

WHAT DO YOU THINK YOUR MOM AND DAD HAVE IN COMMON?

Both don't want any more kids.

-- Lori, age 8

WHAT DO MOST PEOPLE DO ON A DATE?

Dates are for having fun, and people should use them to get to know each other. Even boys have something to say if you listen long enough.

-- Lynnette, age 8 (isn't she a treasure)

On the first date, they just tell each other lies and that usually gets them interested enough to go for a second date.

-- Martin, age 10

WHAT WOULD YOU DO ON A FIRST DATE THAT WAS TURNING SOUR?

I'd run home and play dead. The next day I would call all the newspapers and make sure they wrote about me in all the dead columns

-- Craig, age 9

WHEN IS IT OKAY TO KISS SOMEONE?

When they're rich.

-- Pam, age 7

The law says you have to be eighteen, so I wouldn't want to mess with that.

- - Curt, age 7

The rule goes like this: If you kiss someone, then you should marry them and have kids with them. It's the right thing to do.

-- Howard, age 8

IS IT BETTER TO BE SINGLE OR MARRIED?

It's better for girls to be single but not for boys. Boys need someone to clean up after them.

-- Anita, age 9 (bless you child)

HOW WOULD THE WORLD BE DIFFERENT IF PEOPLE DIDN'T GET MARRIED?

There sure would be a lot of kids to explain, wouldn't there?

-- Kelvin, age 8

And the #1 Favorite is........

HOW WOULD YOU MAKE A MARRIAGE WORK?

Tell your wife that she looks pretty, even if she looks like a dump truck.

-- Ricky, age 10

History 101

For those that don't know about history ... Here is a condensed version:

Humans originally existed as members of small bands of nomadic hunters/gatherers. They lived on deer in the mountains during the summer and would go to the coast and live on fish and lobster in the winter.

The two most important events in all of history were the invention of beer and the invention of the wheel. The wheel was invented to get man to the beer. These were the foundation of modern civilization and together were the catalyst for the splitting of humanity into two distinct subgroups:

1. Liberals, and

2. Conservatives.

Once beer was discovered, it required grain and that was the beginning of agriculture. Neither the glass bottle nor aluminum can were invented yet, so while our early humans were sitting around waiting for them to be invented, they just stayed close to the brewery. That's how villages were formed.

Some men spent their days tracking and killing animals to BBQ at night while they were drinking beer. This was the beginning of what is known as the Conservative movement.

Other men who were weaker and less skilled at hunting learned to live off the conservatives by showing up for the nightly BBQ's and doing the sewing, fetching, and hair dressing. This was the beginning of the Liberal movement.

Some of these liberal men eventually evolved into women. The rest became known as girlie-men. Some noteworthy liberal achievements include the domestication of cats, the invention of group therapy, group hugs, and the concept of Democratic voting to decide how to divide the meat and beer that conservatives provided.

Over the years conservatives came to be symbolized by the largest, most powerful land animal on earth, the elephant. Liberals are symbolized by the jackass.

Modern liberals like imported beer (with lime added), but most prefer white wine or imported bottled water. They eat raw fish but like their beef well done. Sushi, tofu, and French food are standard liberal fare. Another interesting evolutionary side note: most of their women have higher testosterone levels than their men. Most social workers, personal injury attorneys, journalists, dreamers in Hollywood and group therapists are liberals. Liberals invented the designated hitter rule because it wasn't fair to make the pitcher also bat.

Conservatives drink domestic beer, mostly Bud. They eat red meat and still provide for their women. Conservatives are big-game hunters, rodeo cowboys,lumberjacks, construction workers, f iremen, medical doctors, police officers, corporate executives, athletes, members of the military, airline pilots and generally anyone who works productively. Conservatives who own companies hire other conservatives who want to work for a living.

Liberals produce little or nothing. They like to govern the producers and decide what to do with the production. Liberals believe Europeans are more enlightened than Americans. That is why most of the liberals remained in Europe when conservatives were coming to America . They crept in after the Wild West was tamed and created a business of trying to get more for nothing.

Here ends today's lesson in world history:

It should be noted that a Liberal may have a momentary urge to angrily respond to the above before forwarding it.

A Conservative will simply laugh and be so convinced of the absolute truth of this history that it will be forwarded immediately to other true believers and to more liberals just to tick th em off.

And there you have it. Let your next action reveal your true self.

Humans originally existed as members of small bands of nomadic hunters/gatherers. They lived on deer in the mountains during the summer and would go to the coast and live on fish and lobster in the winter.

The two most important events in all of history were the invention of beer and the invention of the wheel. The wheel was invented to get man to the beer. These were the foundation of modern civilization and together were the catalyst for the splitting of humanity into two distinct subgroups:

1. Liberals, and

2. Conservatives.

Once beer was discovered, it required grain and that was the beginning of agriculture. Neither the glass bottle nor aluminum can were invented yet, so while our early humans were sitting around waiting for them to be invented, they just stayed close to the brewery. That's how villages were formed.

Some men spent their days tracking and killing animals to BBQ at night while they were drinking beer. This was the beginning of what is known as the Conservative movement.

Other men who were weaker and less skilled at hunting learned to live off the conservatives by showing up for the nightly BBQ's and doing the sewing, fetching, and hair dressing. This was the beginning of the Liberal movement.

Some of these liberal men eventually evolved into women. The rest became known as girlie-men. Some noteworthy liberal achievements include the domestication of cats, the invention of group therapy, group hugs, and the concept of Democratic voting to decide how to divide the meat and beer that conservatives provided.

Over the years conservatives came to be symbolized by the largest, most powerful land animal on earth, the elephant. Liberals are symbolized by the jackass.

Modern liberals like imported beer (with lime added), but most prefer white wine or imported bottled water. They eat raw fish but like their beef well done. Sushi, tofu, and French food are standard liberal fare. Another interesting evolutionary side note: most of their women have higher testosterone levels than their men. Most social workers, personal injury attorneys, journalists, dreamers in Hollywood and group therapists are liberals. Liberals invented the designated hitter rule because it wasn't fair to make the pitcher also bat.

Conservatives drink domestic beer, mostly Bud. They eat red meat and still provide for their women. Conservatives are big-game hunters, rodeo cowboys,lumberjacks, construction workers, f iremen, medical doctors, police officers, corporate executives, athletes, members of the military, airline pilots and generally anyone who works productively. Conservatives who own companies hire other conservatives who want to work for a living.

Liberals produce little or nothing. They like to govern the producers and decide what to do with the production. Liberals believe Europeans are more enlightened than Americans. That is why most of the liberals remained in Europe when conservatives were coming to America . They crept in after the Wild West was tamed and created a business of trying to get more for nothing.

Here ends today's lesson in world history:

It should be noted that a Liberal may have a momentary urge to angrily respond to the above before forwarding it.

A Conservative will simply laugh and be so convinced of the absolute truth of this history that it will be forwarded immediately to other true believers and to more liberals just to tick th em off.

And there you have it. Let your next action reveal your true self.

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

Monday, August 18, 2008

It's for the simple, stupid!

Continued from Part 2

Before we begin our analysis of his Trinitarian theology, it will be helpful for us to consider Luther’s own explanation of the “simplicity” of his exposition of the Apostles' Creed. This should serve to channel our own study, insuring that we do not misuse Luther’s words.

First, Luther writes for children and those who would teach children. Introducing the three articles of the Creed Luther says, “But in order that it might be easily and simply grasped, as it is to be taught to children, we shall briefly sum up the entire Creed in three articles, according to the three persons of the Godhead. . .” (Large Catechsim II, 6). The goal is to teach “young pupils . . . the most necessary points. ” (LC II, 12). When Luther mentions his very cursory treatment of the substance of the Second Article, he explains, “But the proper place to explain all these different points is not in the short children’s sermon, but in the longer sermons over the whole year. . .” (LC II, 32). The substance of the teaching in this article is “so rich and expansive” that we can never learn it fully (LC II, 33).

First, Luther writes for children and those who would teach children. Introducing the three articles of the Creed Luther says, “But in order that it might be easily and simply grasped, as it is to be taught to children, we shall briefly sum up the entire Creed in three articles, according to the three persons of the Godhead. . .” (Large Catechsim II, 6). The goal is to teach “young pupils . . . the most necessary points. ” (LC II, 12). When Luther mentions his very cursory treatment of the substance of the Second Article, he explains, “But the proper place to explain all these different points is not in the short children’s sermon, but in the longer sermons over the whole year. . .” (LC II, 32). The substance of the teaching in this article is “so rich and expansive” that we can never learn it fully (LC II, 33).

This is no doubt a note to pastors, reminding them to adjust the content of their sermons appropriately according to the situation and audience. Nevertheless, it also serves as a challenge to Luther scholars not to push Luther’s own catechetical formulations too far. His exposition of the catechism was not designed to answer the kind of questions that Trinitarian theologians ask today—or even the kinds of questions asked in his own day!—it was designed for the instruction of children and young students.

Second, Luther’s exposition of the Creed is not only aimed at children and young students, but it also attempts to provide instruction for ordinary people. Luther often uses the adjective einfältig (“simple,” “plain,” “naïve,” even “artless”) as well as the noun Einfältig to describe his intended audience. Care should be taken to ascertain the level of the student so that one can teach them appropriately.

At the beginning of his comments on the First Article, Luther admits that “for the learned and the somewhat more advanced, however, all three articles can be treated more fully and divided into as many parts as there are words” (LC II, 12). Concluding his very brief discussion of the meaning of the first article, Luther comments, “It is as much as the simple [den Einfältigen] need to learn at first. . .” (LC II, 24). Luther concludes his exposition of the Creed with the following caveat: “For the present this is enough concerning the Creed to lay a foundation for simple people [einen Grund zu legen für die Einfältigen], so that one does not overburden them. When they understand the essentials of it, they may pursue it themselves, relating what they learn in the Scriptures to these teachings, growing and increasing forever more into a richer understanding. For concerning these things we have to learn and preach daily, as long as we live” (LC II, 70).

These two target audiences (children and common people) constrain Luther’s theological exposition. This knowledge ought to serve to restrain our own theological speculation. The student of Luther must remember that the simplicity of his catechetical exposition is pedagogically constrained. He is writing a primer for children (SC) and a manual for pastors (and fathers) who teach this primer to children and common folk (LC). I think we can pretty well safely assume that Luther never dreamed of the day when academic theologians would pour over his “simple” exposition of the Creed looking for deep theological and philosophical structures. After all, Luther describes his own elucidation of the Creed as “briefly running over the words” (LC II, 8). That does not mean, of course, that a scholarly examination of Luther’s writings is inappropriate; it means that scholars who do the examining would do well not to push to find evidence of something more cryptic and sophisticated than Luther himself would probably have intended.

Furthermore, the simplicity of Luther’s treatment of the Trinitarian nature of God follows from the obvious fact that Luther is not setting forth a theology of the Trinity per se; rather, he is expounding the Trinitarian content of the Christian faith as it is articulated in the Apostles’ Creed. Surely Luther himself did not intend to incorporate into his catechetical writings anything like a comprehensive theology of the Trinity, or even everything important he might have said about the Trinity were he to address the topic specifically. He is not only writing with a specific audience in mind, he is also working with a particular text and his Trinitarian theology will be bound, in some sense, by the limitations of the text of the Apostles’ Creed.

Moreover, Luther does appear to allow for a more sophisticated theology of the Trinity. When he sums up the importance and usefulness of the Creed for our knowledge of the “whole divine essence, will, and work,” he notes that such an exalted topic is nevertheless described in “altogether brief and yet regal words” (LC II, 63). There are later sermons where Luther’s purpose is to set forth the doctrine of the Trinity itself, but that is not the purpose of his catechetical explanation of the Creed. All of which serves to remind the modern student of Luther that Luther’s entire doctrine of the Trinity must not be thought to be contained here in his catechetical exposition of the Creed. We need not necessarily fault Luther for leaving out of his exposition points that we might think important. And we must not attempt to discover points that Luther never intended to make. Care must be exercised so as not to artificially build up a Trinitarian theology from the catechisms alone without consulting his later writings. It is our purpose now to examine these kurtzen und doch reichen Worten (“short and yet regal words”) in order to outline Luther’s rich and majestically simple doctrine of the Trinity.

Go to Part III.

Before we begin our analysis of his Trinitarian theology, it will be helpful for us to consider Luther’s own explanation of the “simplicity” of his exposition of the Apostles' Creed. This should serve to channel our own study, insuring that we do not misuse Luther’s words.

First, Luther writes for children and those who would teach children. Introducing the three articles of the Creed Luther says, “But in order that it might be easily and simply grasped, as it is to be taught to children, we shall briefly sum up the entire Creed in three articles, according to the three persons of the Godhead. . .” (Large Catechsim II, 6). The goal is to teach “young pupils . . . the most necessary points. ” (LC II, 12). When Luther mentions his very cursory treatment of the substance of the Second Article, he explains, “But the proper place to explain all these different points is not in the short children’s sermon, but in the longer sermons over the whole year. . .” (LC II, 32). The substance of the teaching in this article is “so rich and expansive” that we can never learn it fully (LC II, 33).

First, Luther writes for children and those who would teach children. Introducing the three articles of the Creed Luther says, “But in order that it might be easily and simply grasped, as it is to be taught to children, we shall briefly sum up the entire Creed in three articles, according to the three persons of the Godhead. . .” (Large Catechsim II, 6). The goal is to teach “young pupils . . . the most necessary points. ” (LC II, 12). When Luther mentions his very cursory treatment of the substance of the Second Article, he explains, “But the proper place to explain all these different points is not in the short children’s sermon, but in the longer sermons over the whole year. . .” (LC II, 32). The substance of the teaching in this article is “so rich and expansive” that we can never learn it fully (LC II, 33). This is no doubt a note to pastors, reminding them to adjust the content of their sermons appropriately according to the situation and audience. Nevertheless, it also serves as a challenge to Luther scholars not to push Luther’s own catechetical formulations too far. His exposition of the catechism was not designed to answer the kind of questions that Trinitarian theologians ask today—or even the kinds of questions asked in his own day!—it was designed for the instruction of children and young students.

Second, Luther’s exposition of the Creed is not only aimed at children and young students, but it also attempts to provide instruction for ordinary people. Luther often uses the adjective einfältig (“simple,” “plain,” “naïve,” even “artless”) as well as the noun Einfältig to describe his intended audience. Care should be taken to ascertain the level of the student so that one can teach them appropriately.

At the beginning of his comments on the First Article, Luther admits that “for the learned and the somewhat more advanced, however, all three articles can be treated more fully and divided into as many parts as there are words” (LC II, 12). Concluding his very brief discussion of the meaning of the first article, Luther comments, “It is as much as the simple [den Einfältigen] need to learn at first. . .” (LC II, 24). Luther concludes his exposition of the Creed with the following caveat: “For the present this is enough concerning the Creed to lay a foundation for simple people [einen Grund zu legen für die Einfältigen], so that one does not overburden them. When they understand the essentials of it, they may pursue it themselves, relating what they learn in the Scriptures to these teachings, growing and increasing forever more into a richer understanding. For concerning these things we have to learn and preach daily, as long as we live” (LC II, 70).

These two target audiences (children and common people) constrain Luther’s theological exposition. This knowledge ought to serve to restrain our own theological speculation. The student of Luther must remember that the simplicity of his catechetical exposition is pedagogically constrained. He is writing a primer for children (SC) and a manual for pastors (and fathers) who teach this primer to children and common folk (LC). I think we can pretty well safely assume that Luther never dreamed of the day when academic theologians would pour over his “simple” exposition of the Creed looking for deep theological and philosophical structures. After all, Luther describes his own elucidation of the Creed as “briefly running over the words” (LC II, 8). That does not mean, of course, that a scholarly examination of Luther’s writings is inappropriate; it means that scholars who do the examining would do well not to push to find evidence of something more cryptic and sophisticated than Luther himself would probably have intended.

Furthermore, the simplicity of Luther’s treatment of the Trinitarian nature of God follows from the obvious fact that Luther is not setting forth a theology of the Trinity per se; rather, he is expounding the Trinitarian content of the Christian faith as it is articulated in the Apostles’ Creed. Surely Luther himself did not intend to incorporate into his catechetical writings anything like a comprehensive theology of the Trinity, or even everything important he might have said about the Trinity were he to address the topic specifically. He is not only writing with a specific audience in mind, he is also working with a particular text and his Trinitarian theology will be bound, in some sense, by the limitations of the text of the Apostles’ Creed.

Moreover, Luther does appear to allow for a more sophisticated theology of the Trinity. When he sums up the importance and usefulness of the Creed for our knowledge of the “whole divine essence, will, and work,” he notes that such an exalted topic is nevertheless described in “altogether brief and yet regal words” (LC II, 63). There are later sermons where Luther’s purpose is to set forth the doctrine of the Trinity itself, but that is not the purpose of his catechetical explanation of the Creed. All of which serves to remind the modern student of Luther that Luther’s entire doctrine of the Trinity must not be thought to be contained here in his catechetical exposition of the Creed. We need not necessarily fault Luther for leaving out of his exposition points that we might think important. And we must not attempt to discover points that Luther never intended to make. Care must be exercised so as not to artificially build up a Trinitarian theology from the catechisms alone without consulting his later writings. It is our purpose now to examine these kurtzen und doch reichen Worten (“short and yet regal words”) in order to outline Luther’s rich and majestically simple doctrine of the Trinity.

Go to Part III.

Sunday, August 17, 2008

Image of the Day

This is a silly image, I know. But it's one that meets the requirements of a contest I am in. There are 27 photographers who've made it this far. We have two weeks to enter an image that fits this theme: "the elements." The winner gets a new Nikon D300 and a lifetime pro account at SmugMug. Coolness. This is my tongue-in-cheek submission.

Friday, August 15, 2008

Thursday, August 14, 2008

St. Louis Photo Walk

We now have 40 confirmed participants for the St. Louis enactment of Scott Kelby's Worldwide Photo Walk. There are still 10 more openings!

Luther’s Trinitarian Doctrine Prior to his Catechetical Work (—1528)

Continued from Part 1

Luther, like Augustine and Calvin, received the traditional substance of doctrine of the Trinity from the Early Church Councils while reserving the right to criticize some of the traditional philosophical terminology used to formulate the doctrine. Luther only infrequently discusses the subject of the Trinity as a distinct topic or doctrine. Consequently we have no systematic presentation of the doctrine of the Trinity by Luther himself as we have, for example, in Melanchthon’s later editions of the Loci and or in Calvin’s Institutes.

Nevertheless, Luther unambiguously embraces the orthodox Trinitarian doctrine of the church. Luther’s Christmas sermon of 1514, provides us with an early reference to Luther’s commitment to classic Trinitarianism. At this stage in Luther’s development we find him following Augustine’s lead by introducing various analogies as aids for understanding the problem of the Trinity. Luther, however, begins to break with long-standing scholastic categories in that his analogies are not restricted to the realm of human psychology. Prenter interprets:

Of course, we do find Luther faithfully confessing the doctrine of the Trinity whenever he has the opportunity to craft a confession of faith. As Lohse puts it: “Whenever Luther formulated confessions or articles of faith, he regularly began with the doctrine of God in its Trinitarian form. For this reason it would seem appropriate to give the doctrine of God the central position in Luther’s theology." Lohse may be correct about the “centrality” of Luther’s doctrine of the Trinity, but such an assertion will certainly not be established merely by noting that Luther always “began” his confessions with an article on the Trinity. Just about everyone’s confession—Roman Catholic, Reformed, and Lutheran—contained an article on the Trinity somewhere near the top. What does this prove? Can one really establish doctrinal primacy or centrality in this way? Whether the doctrine of the Trinity is “central” in Luther’s pre-catechetical writings can be established only by examining how Luther utilizes the Trinity when it really counts. Placing an article on the Trinity at the head of one’s confession evidences Luther’s faithfulness to received doctrine, nothing more.

The evidence indicates that sometime during the years 1520-23, Luther began to articulate the reciprocal, dynamic relationship between what we now call the “economic” and “ontological” Trinity with increasing clarity and profundity. It is evident already in his A Short Form of the Faith (1520). [I don't have an English translation of this work in front of me, only the German. I've been away from my German for a while, but I'll see if I can translate it on the fly.] In this little work Luther is concerned not just with the proper formulas and terminology describing the Trinity. When he is explaining the Creed we begin to see evidence of Luther’s desire to wring out of the doctrine all of its soteriological significance for the believer. Luther may have shared certain dogmatical Trinitarian formulations with his opponents, but they are now beginning to function for Luther in a way that they did not for the Late Medieval church. Evidence of this occurs only when Luther begins to explain the Second Article. After quoting the Creed, Luther explains:

Lohse makes a suggestive comment in reference to Luther’s statement on the Trinity in the Smalcald Articles that may help explain the substance and function of the "but also" clauses in this early work. At the conclusion of Part I of the Smalcald Articles (treating “the sublime articles of the divine majesty”) Luther notes: “These articles are not matters of dispute or contention, for both parties *believe and* confess them. Therefore, it is not necessary to treat them at greater length.” After noting that the words “believe and” were crossed out by Luther and not included in the official printed texts of the Articles, Lohse explains, “Naturally, Luther did not intend to imply that the dogma of the Trinity was not firmly maintained in the Roman Church. For Luther, however, faith in the triune God simultaneously required a specific doctrine of the human person and a specific doctrine of salvation; that is, faith in the triune God required the Reformation doctrine of justification. For Luther, simply accepting dogmas as true was not enough.”

Luther, then, not only affirms that the each of the Articles of the Apostle’s Creed are true, he not only assents to the received doctrinal explanations of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, he believes they bear significantly upon the meaning of the Christian’s relationship with God. The ontological relations are only significant because they can only be known and confessed insofar as the Holy Spirit brings us to the Father through Christ. In 1520, these ideas were in the process of germinating. When Luther returns eight years later to the Creed and its exposition he is prepared to communicate the biblical Trinitarian Gospel to “simple” Christians in his catechetical writing and preaching.

Go to Part II.

Luther, like Augustine and Calvin, received the traditional substance of doctrine of the Trinity from the Early Church Councils while reserving the right to criticize some of the traditional philosophical terminology used to formulate the doctrine. Luther only infrequently discusses the subject of the Trinity as a distinct topic or doctrine. Consequently we have no systematic presentation of the doctrine of the Trinity by Luther himself as we have, for example, in Melanchthon’s later editions of the Loci and or in Calvin’s Institutes.

Nevertheless, Luther unambiguously embraces the orthodox Trinitarian doctrine of the church. Luther’s Christmas sermon of 1514, provides us with an early reference to Luther’s commitment to classic Trinitarianism. At this stage in Luther’s development we find him following Augustine’s lead by introducing various analogies as aids for understanding the problem of the Trinity. Luther, however, begins to break with long-standing scholastic categories in that his analogies are not restricted to the realm of human psychology. Prenter interprets:

In scholasticism the doctrine of the Trinity and anthropology are united in a manner that makes the inner essence of the human soul a reflection of the essence of God. Already in the sermon of 1514, we notice that Luther is beginning to deviate from this view, which also was very contrary to his concept of sin which held that the inner soul was touched by the fall. And when the concept motis, which also later plays a part in Luther’s presentation of the doctrine of the Trinity gets into the foreground, it seems to prove that the Trinity doctrine is no longer oriented on the basis of God’s passive nature as reflected in man’s process of understanding, but on the basis of God’s activity in revelation as it is seen in the history of revelation (Regin Prenter, Spiritus Creator, trans. John Jensen [Philadelphia: Mulenberg Press, 1953], 175).Prenter’s comments are plausible. Luther does seem to be moving beyond traditional scholastic categories. Even so, he still has a long way to travel before he arrives at formulations that eschew the language of philosophy and metaphysics. One might indeed wonder whether Luther’s Aristotelian analogies are truly proleptic or whether we are only too willing to allow our own active imaginations anachronistically to read into Luther’s earlier works vestigia of his later insights. One thing is clear. Luther’s doctrine of the Trinity is at this point only very loosely related to God’s revelation of his fullness in salvation history. The same kind of analysis might be made of Luther’s doctrine of the Trinity in the his early lectures on Romans (1515-16), Galatians (1519), and his Dictata super Psalterium (1513-1515). Although Luther sometimes uses language that might imply a creatively dynamic way of speaking about the Trinity in relationship to man, his Trinitarianism remains largely bound to traditional categories of analogy and ontology.

Of course, we do find Luther faithfully confessing the doctrine of the Trinity whenever he has the opportunity to craft a confession of faith. As Lohse puts it: “Whenever Luther formulated confessions or articles of faith, he regularly began with the doctrine of God in its Trinitarian form. For this reason it would seem appropriate to give the doctrine of God the central position in Luther’s theology." Lohse may be correct about the “centrality” of Luther’s doctrine of the Trinity, but such an assertion will certainly not be established merely by noting that Luther always “began” his confessions with an article on the Trinity. Just about everyone’s confession—Roman Catholic, Reformed, and Lutheran—contained an article on the Trinity somewhere near the top. What does this prove? Can one really establish doctrinal primacy or centrality in this way? Whether the doctrine of the Trinity is “central” in Luther’s pre-catechetical writings can be established only by examining how Luther utilizes the Trinity when it really counts. Placing an article on the Trinity at the head of one’s confession evidences Luther’s faithfulness to received doctrine, nothing more.

The evidence indicates that sometime during the years 1520-23, Luther began to articulate the reciprocal, dynamic relationship between what we now call the “economic” and “ontological” Trinity with increasing clarity and profundity. It is evident already in his A Short Form of the Faith (1520). [I don't have an English translation of this work in front of me, only the German. I've been away from my German for a while, but I'll see if I can translate it on the fly.] In this little work Luther is concerned not just with the proper formulas and terminology describing the Trinity. When he is explaining the Creed we begin to see evidence of Luther’s desire to wring out of the doctrine all of its soteriological significance for the believer. Luther may have shared certain dogmatical Trinitarian formulations with his opponents, but they are now beginning to function for Luther in a way that they did not for the Late Medieval church. Evidence of this occurs only when Luther begins to explain the Second Article. After quoting the Creed, Luther explains:

I believe that Jesus alone is truly the one Son of God, in one divine nature and essence as the eternally begotten, but also that with the Father he created all things, and with my humanity is Lord over all. .The “but also” might give the impression that the two parts of this confession concerning Jesus Christ—Christ in se and Christ pro me— are only very loosely connected. Luther does not explicitly explain the relationship between these two dimensions of Christology. Later, as we shall see, he drops the “but also” language altogether and unites what Christ “is” and what Christ “does” in the strongest possible way. Here Luther is struggling to mine these ontological statements ("divine nature and essence") for their significance pro me. This same language and order occurs in Luther’s explanation of the Third Article. One can perceive here the seeds of what will shortly blossom into a profound doctrine of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit’s unified work of salvation pro me. Luther is not satisfied with explicating ontological relations between the Persons. This is not the real meaning of the Trinity.

Lohse makes a suggestive comment in reference to Luther’s statement on the Trinity in the Smalcald Articles that may help explain the substance and function of the "but also" clauses in this early work. At the conclusion of Part I of the Smalcald Articles (treating “the sublime articles of the divine majesty”) Luther notes: “These articles are not matters of dispute or contention, for both parties *believe and* confess them. Therefore, it is not necessary to treat them at greater length.” After noting that the words “believe and” were crossed out by Luther and not included in the official printed texts of the Articles, Lohse explains, “Naturally, Luther did not intend to imply that the dogma of the Trinity was not firmly maintained in the Roman Church. For Luther, however, faith in the triune God simultaneously required a specific doctrine of the human person and a specific doctrine of salvation; that is, faith in the triune God required the Reformation doctrine of justification. For Luther, simply accepting dogmas as true was not enough.”

Luther, then, not only affirms that the each of the Articles of the Apostle’s Creed are true, he not only assents to the received doctrinal explanations of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, he believes they bear significantly upon the meaning of the Christian’s relationship with God. The ontological relations are only significant because they can only be known and confessed insofar as the Holy Spirit brings us to the Father through Christ. In 1520, these ideas were in the process of germinating. When Luther returns eight years later to the Creed and its exposition he is prepared to communicate the biblical Trinitarian Gospel to “simple” Christians in his catechetical writing and preaching.

Go to Part II.

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

The Trinity for the Simple

Twelve years ago I wrote an interesting (to me!) paper on Luther's doctrine of the Trinity for a graduate seminar class at Concordia on Luther's Small and Large Catechism. The title of the paper was "Die Dreifaltigkeit für die Einfältigen: Luther’s Catechetical Doctrine of the Trinity." The German phrase means "The Trinity for the Simple."

Twelve years ago I wrote an interesting (to me!) paper on Luther's doctrine of the Trinity for a graduate seminar class at Concordia on Luther's Small and Large Catechism. The title of the paper was "Die Dreifaltigkeit für die Einfältigen: Luther’s Catechetical Doctrine of the Trinity." The German phrase means "The Trinity for the Simple." I've been looking over my past work on the Trinity lately, wondering if I might actually be able finally to finish that book I've always wanted to write. We'll see. At any rate, I'm going to simplify (remove all the German and dispense with the academic references) and update this old essay of mine and publish it here as a series of posts. Perhaps someone will find it helpful.

Now, one caveat: my observations and analyses are dated, especially with regard to the literature available to me in 1996 on Luther's doctrine of the Trinity. There's been some advance in Luther studies re: the Trinity. So if I had the time to do the research, I would probably qualify some of the first few paragraphs. So here goes.

When the Lutheran theologian Walter Elert describes Luther’s traditional theology of the Trinity, he makes this charge: “In general, the doctrine of the Trinity came to a standstill in his theology like an erratic boulder.” The French Roman Catholic theologian Yves Congar’s opinion was similar. “Luther is not a man for the mystery of the Trinity.” Edmund J. Fortman’s The Triune God devotes only four of its 380 pages to the Reformation understanding of the Trinity: Luther and Melanchthon are treated in less than one page each. Fortman’s conclusion: “His [Luther’s] Trinitarian doctrine remained largely a simple, devout expression of his belief in the traditional dogma.”

One might have anticipated a more positive evaluation of Luther’s doctrine of the Trinity to emerge in the wake of the modern renewal of Trinitarian theology in the last few decades. So far, however, recent opinions appear not to have altered much. The contemporary Roman Catholic Trinitarian theologian Edmund J. Hill says, “In Luther’s own writings, the Trinity plays only a very minor theological role, serving largely to buttress his real concerns, which are those of faith and justification.” At least Hill says something about Luther’s doctrine of the Trinity. Most contemporary Trinitarian theologians ignore Luther altogether on this subject. Nobody, as far as I have been able to discover, even notices the theological potential in the Trinitarian shape of Luther’s Small and Large Catechisms.

Was Luther’s doctrine of the Trinity as unsophisticated and slavishly tradition-bound as these authors would lead us to believe? Did Luther’s use of the Trinity have no more profound motivation than an unselfconscious “traditionalism”? Does the doctrine of the Trinity appear in Luther’s catechetical work as something sterile and inert? Granted that Luther does not utilize most of the traditional metaphysical terms and distinctions available to him as heir of a rich repository of Western Trinitarian reflection, does this necessarily imply that his Trinitarian theology is unsophisticated, artless, and ultimately barren? That it has no deep roots in the historical church’s Trinitarian heritage? Why indeed does Luther “neglect” certain aspects of classical Trinitarian theology? Does that neglect arise self-consciously as a critique of Scholastic/Augustinian Trinitarian speculation or does it simply point to Luther’s own theological ignorance, possibly even stubbornness?